Generally, it’s agreed that improving health equity is a desirable goal. Individuals, groups, and society as a whole would benefit from everyone having the opportunity to live a healthy life. Individuals and communities would thrive. Economies and societies would flourish. The cost of healthcare would no longer be a drain on society.

Since the mid-1960s efforts were made in the US for addressing social, economic, environmental, and behavioral barriers to health equity. Yet, the COVID-19 health emergency pandemic has portrayed the various health disparities and inequities that persist.

Perhaps it’s time to look beyond the current, established thinking around how to address health disparities and embrace some new thinking to get us moving toward achieving health equity.

Health Equity, Defined

Both healthcare and governmental leaders recognize health equity as a key goal for improving people’s quality of life. However, there is still plenty of room for debate when it comes to defining exactly what that means and how to go about it. Efforts to address persistent social, economic, environmental, and behavioral barriers in healthcare have gone on for decades, and yet disparities persist.

Health equity is often described as providing all people the opportunity to attain the highest level of health possible. To the layperson, this translates to a long life, filled with good health and positive contributions to society. To the public health professional, this translates to health policies, funding, and practices that drive improved health statistics.

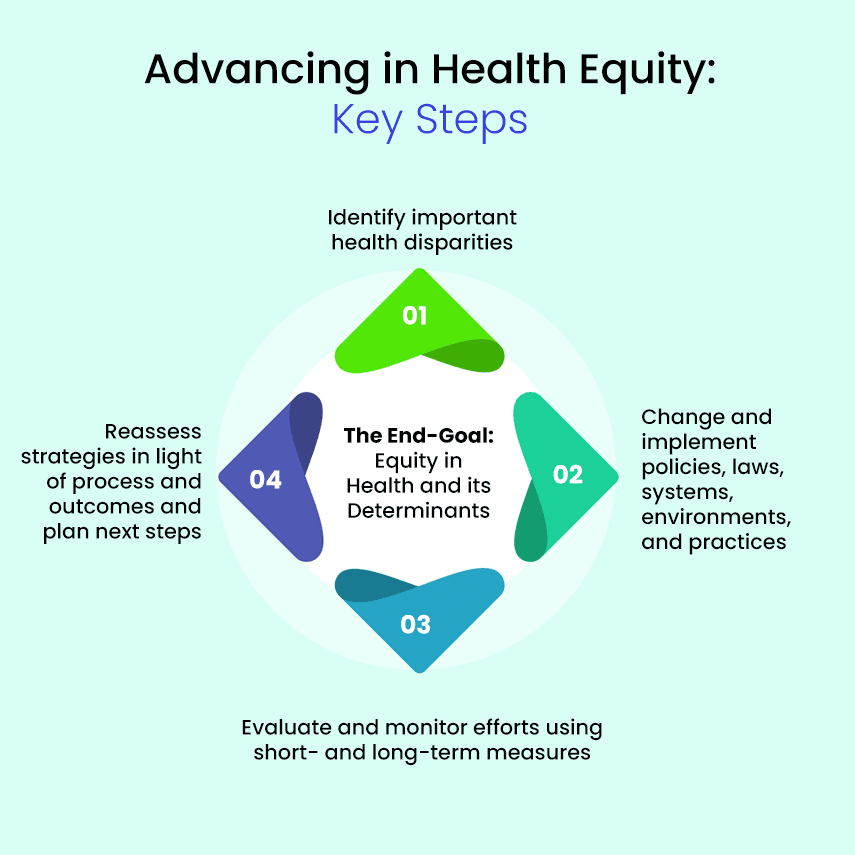

At a strategic level, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation documented four key steps to advancing health equity in its What Is Health Equity? report.

They are:

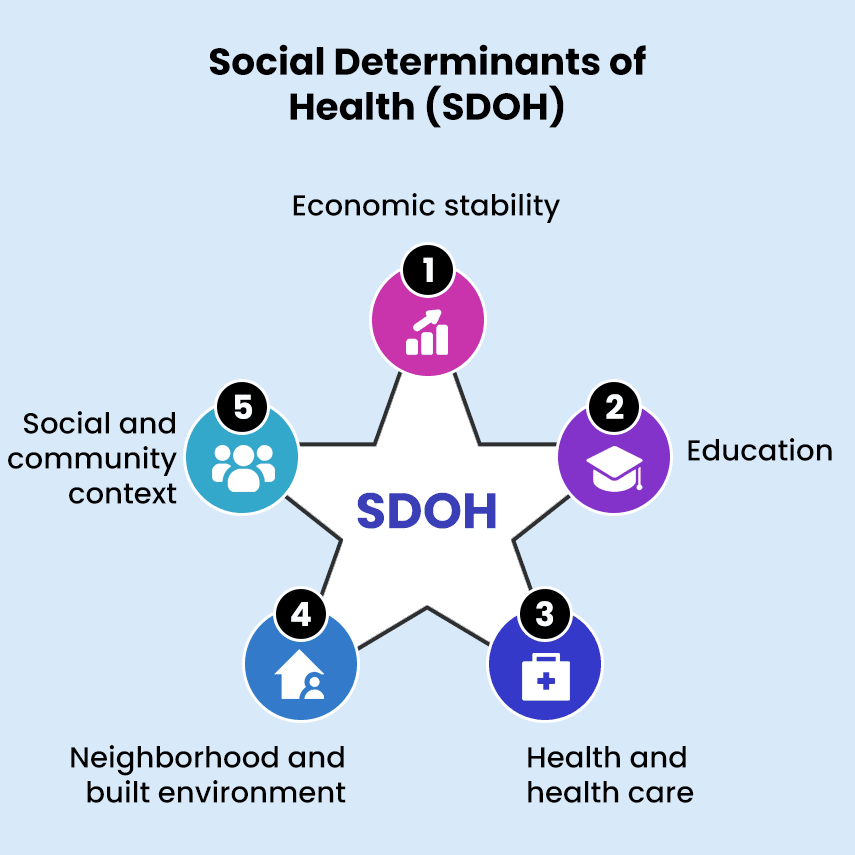

Health disparities are a particular type of health variation that adversely affects groups of people. They are closely linked to economic, social, and/or environmental factors and are often discussed as part of the social determinants of health (SDOH).

Changing policies and practices in order to eliminate unfair and avoidable disparities is seen as the key activity that will move us toward fostering health equity.

However, policymakers and healthcare leaders don’t have a single, agreed-upon framework for health equity on which to base their work. In Health Equity and Health Disparities Environmental Scan, the HHS presents no less than six frameworks currently in use by various organizations and agencies.

This leaves us with this list of general areas, referred to as the social determinant of health (SDOH) where evidence of disparities can be seen:

What COVID-19 Uncovered

One of the unexpected results of COVID-19 has been bringing existing health disparities to the forefront of the healthcare discussion in the U.S. Response to the federally-declared health emergency included gathering and reporting on detailed health data.

In tracking the spread of COVID and the healthcare response gaps in care and resources that translated to worse outcomes for some communities were uncovered. A straight line could be drawn between limited access to healthcare and higher mortality rates in these communities.

Additionally, federal investment in home and community-based (HCBC) services encouraged community healthcare agencies to rethink healthcare delivery and adopt new practices, most notably telehealth, in response to COVID-19. Health insurance enrollment expanded for groups who previously went uncovered. An influx of federal funds paid for many of these innovations.

Nonetheless, these changes aren’t expected to be enough to overcome historical disparities. And with the health emergency winding down and the extra federal funding coming to an end, healthcare leaders are left asking themselves how we can, in the long term, capitalize on the lessons learned from and the investments made during COVID.

Many familiar strategies continue to be part of the health equity conversation:

- Prioritizing health equity as a goal in hiring and practice

- Share best practices and encourage adopting effective strategies

- Staff training in unconscious bias and cultural sensitivity

- Tap into federal support

All these strategies have been tried to varying degrees, but none has proved enough to permanently move the needle on addressing disparities and encouraging health equity. One reason may be that none of them address the root cause of poor patient experience, i.e., lack of trust and poor communication.

Coming out of the COVID-19 health emergency, several additional strategies with the potential to build trust and improve communication have been added to the discussion.

These include

- Rethinking healthcare processes so that they are more inclusive

- Adopting and adapting technology for better communications and stronger connections

- Recognizing that some traditional measures don’t accurately capture the full picture

- Understanding more completely the people and communities being served

This approach is still based on a framework that keeps healthcare and how it’s delivered separately from the community at large. The SDOH are treated as discrete factors — each to be addressed on its own without necessarily taking into context the greater community. Although interrelated, potential synergies (that could move us toward health equity at a faster pace) haven’t been successfully exploited.

Rethinking How to Further Health Equity

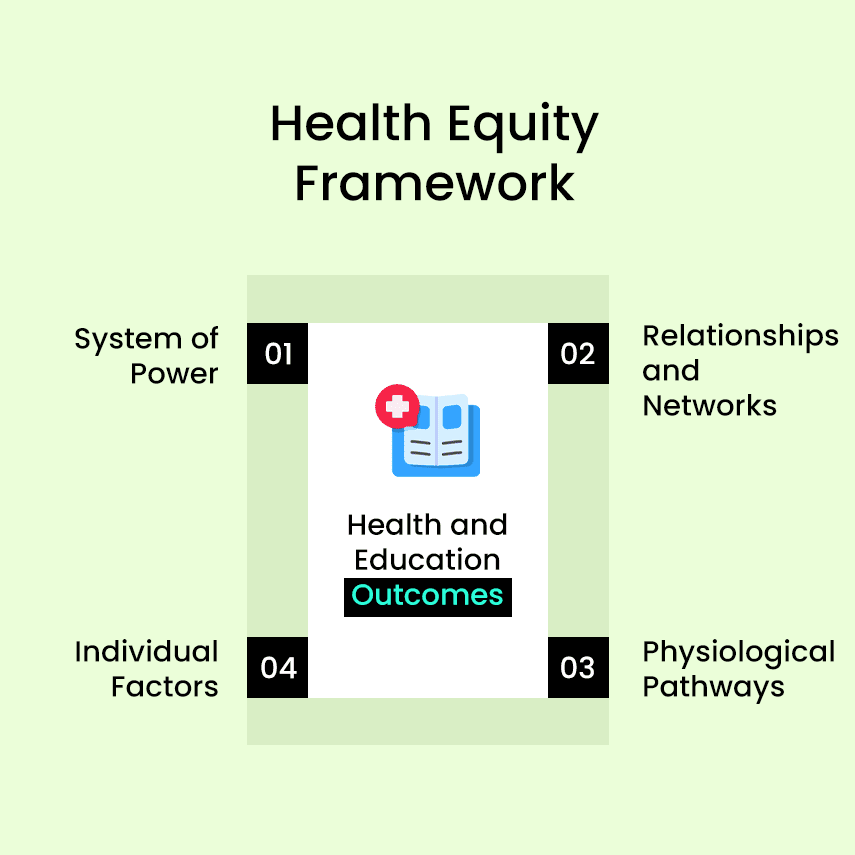

A new health equity framework has been put forth. One that highlights spheres of influence and how the dynamics of systems of power and networks can be used to address disparities. Going beyond merely identifying and measuring the sources of inequity, this framework points healthcare organizations toward taking on an expanded role, well beyond just provisioning healthcare, in their communities to encourage health equity.

Healthcare organizations need to look beyond their provider role and embrace roles that make them anchoring institutions in their greater communities. As employers, partners, and advocates, healthcare organizations wield a lot of power and influence in their communities. The influence can reduce disparities and encourage equity.

As employers, healthcare organizations can actively recruit and employ underrepresented groups at every level of their operations. Not only does this benefit the employee and their family, but it also creates a tangible connection between the healthcare organization and that employee’s social network and community. This same effect will come from adopting inclusive procurement and contracting policies.

Community and government partnerships give healthcare organizations another opportunity to engage with underrepresented groups. Making room at the table for diverse community representation will bring new perspectives to planning and policy discussions. Over time relationships will build and networks strengthened.

Healthcare organizations are in a unique position to advocate for how and where social services are delivered. Through advocacy they can influence plans and projects that can focus services where they are most needed, bringing better health to every part of their community.

By embracing a culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion healthcare organizations can model and encourage equity in their communities. Listed above are just a few of the ways healthcare organizations can use their influential position to reduce disparities. More importantly, by becoming an anchoring institution for health equity in their communities healthcare organizations will build trust in those communities — addressing the root cause of poor patient experience.

Author's Bio